Case Study: Neutral Ships

Hamburg and Dutch ships in the port of Hamburg, detail from the painting “Hamburg von der Elbseite”, Elias Gallium 1680, Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, Stadtgeschichtlicher Rundgang im 1.OG, Rechte: SHMH, Google Arts & Culture.

Read the Blog by the University of Oldenburg

PR Case Studies: Dr Lucas Haasis

Email: lucas.haasis@uni-oldenburg.de

Homepage: Annika Eileen de Freitas

Prof. Dr Dagmar Freist

Project Director

With the publication of these exemplary ships, we provide an insight into the research potential of the manifold documents surviving as prize papers in The National Archives, UK. More so, we demonstrate the incredible benefit of sorting, cataloguing, digitizing and presenting this vast collection open access for academic research and the interested public which is being made possible by the funding of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities: For the first time, researchers can search the prize papers on document level, on a large scale, and they can establish various relations between documents, captures, court processes, actors, time and place in this beta version of the Portal.

Dr Amanda Bevan

Head of Legal Records and Head of the National Archives' Prize Papers Team

We have uncovered the stories of ships captured by the Royal Navy and privateers in the wars of the 1740s. Any letters on board, for delivery across the seas, were confiscated: the Prize Papers Project is virtually delivering them to and across the world, nearly 300 years later.

Listen to this interview with Amanda Bevan:

Case Study: Neutral Ships

Over the course of 2022 and 2023 the Prize Papers Project will publish representative case studies of documents found on board ships seized by the British during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). We will showcase a selection of exemplary records along with the corresponding court records. The purpose of these case studies is to introduce our visitors to the richness, character and diversity of the Prize Papers collection. All these papers are held in the series HCA 30 and HCA 32 at The National Archives, UK and the documents will be made available online for the first time as digital images with metadata on our open access data portal. Following on from the first case study on French Prizes, this second case study covers the stories of neutral ships captured by the British on suspicion of cooperating with the enemy. Our homepage provides the historical background to the fascinating time capsules of records taken from these ships, which are in many languages and originate from locations across the Atlantic seaboard.

Between 1740 and 1748 many parts of the world were shaken by the War of the Austrian Succession, which raged in Europe, America, Russia, India and the Caribbean.

The military powers involved were the Habsburg Monarchy, Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, Hanover and their allies, who fought against France, Prussia, Spain, Bavaria and their allies. The war at sea mainly involved two colonial powers, Britain and France, which fought each other between 1744–48.

One of the most important war tactics at sea during the War of the Austrian Succession was ship capture.

The seizure of enemy ships was a common tactical warfare practice throughout the early modern period undertaken by those involved. Both navies and privateers carried out this practice. Privateers were privately owned ships carrying a letter of marque from a king or a queen permitting them to capture enemy ships.

During raids privateers and naval vessels mainly captured enemy ships. But they did not shy away from capturing the ships of neutral powers.

These ships were captured ‘under the pretense that the said ship and goods did belong to and were the property of subjects of the French king or other enemies of the crown of Great Britain’, according to official declarations by the British authorities. The British ships and authorities suspected that neutral ships and ports were used to avoid the trade embargo between warring powers, and their suspicions were well founded.

Maritime neutrality meant that an economic power would neither involve itself nor interfere militarily or economically in a prevailing war.

Maritime neutrality was governed by treaties with the belligerents and, in return, ensured the neutral powers and their merchants free movement and trade in the territories and economies of the epoch. In order to fulfill the condition of maritime neutrality in practice, when two ships approached each other, a ship was required not only to fly a neutral flag but also to produce neutral ship’s papers on demand, such as a neutral ship’s passport, a list of goods belonging to neutral merchants, or muster rolls of crew members listing a crew from neutral countries. If a British privateer or naval vessel believed that a neutral ship or even a ship of an ally was carrying enemy goods, then they would likely seize the ship and carry it into a port in England, where the crew would be interrogated.

But neutrality was often negotiable.

Grey areas existed or, in many cases, the boundaries of law shifted or were open to broad interpretation. Definitions of what was permissible were found in practice – and often ultimately decided in court. Maritime courts, such as the English High Court of Admiralty are real treasure troves for finding commercial practices of alleged neutrality. People of all nations also used neutral ships to communicate with people across the divides imposed by war, so they can hold remarkable collections of letters that are more personal in nature. The court's task was to determine whether or not a ship had connections with enemy traders and markets.

The best strategy for captains and the owners of the neutral ships was not to be caught in the act of trading and collaborating with the enemy.

There was a great incentive for the merchants of neutral powers to actively participate in the colonial economies of the time. In some countries, such as France, foreign merchants from neutral powers were even granted privileges, especially in trade with colonial goods. Neutrals were often forbidden from engaging in direct trade with the colonies, but the profit margin was immensely high and participation therefore tempting. On the legal fringe, merchants participated in colonial trade through practices such as shipping or logistic provision, or through commission trade. Merchants could even resort to outright smuggling or sailing under a false flag.

The task of the High Court of Admiralty was to prove whether a captured ship was neutral or deemed a legitimate prize.

This meant that prize-taking was not a lawless act of piracy. On the contrary, laws – typically respected by all parties involved – dictated precisely how and under what circumstances a legal capture should unfold. A ship could only be legally captured if it was possible to prove that it belonged to an enemy party or supported that party’s war effort. The final ruling on the legality of a capture was handed down in court.

Before the court, cogent evidence had to be presented that there was a connection between the ship and the enemy.

The captors had to provide evidence that the captured ships ‘sailed with false, counterfeit passports, under a false flag, with a false connoissement, false papers or with prohibited goods, contrabande’, as it reads in the court records. For the seafarers setting out to take prizes, this meant finding evidence on board the captured ship that proved the captain, crew or ship owner had secretly collaborated with the enemy.

This meant that the captors of neutral ships literally searched and investigated every last scrap of paper on board the captured ship and confiscated almost all papers as evidence.

As often documented in the court records, the officers of the capturing ship turned the captured ship upside down, removing parts of the cargo and searching every corner of the ship. It was common for captains, sailors and merchants to hide their personal belongings or papers in several places on the ship.

For this reason, the surviving records of neutral ships in the Prize Papers collection are often extensive.

These cases of supposedly neutral ships were more complex than the more routine cases of enemy capture, resulting in more diverse records. The home authorities of these ships also often objected to their capture and filed complaints in appeal cases. Court cases involving neutral ships could thus drag on for years – as was the case for the two Hamburg ships published in this launch.

We are now publishing in the portal, as the next case study, the records of six neutral or allied ships captured by the British.

Each sailed under Hamburg or Dutch colours and together they reflect the great diversity of vessels captured alongside those of the belligerents during wartimes.

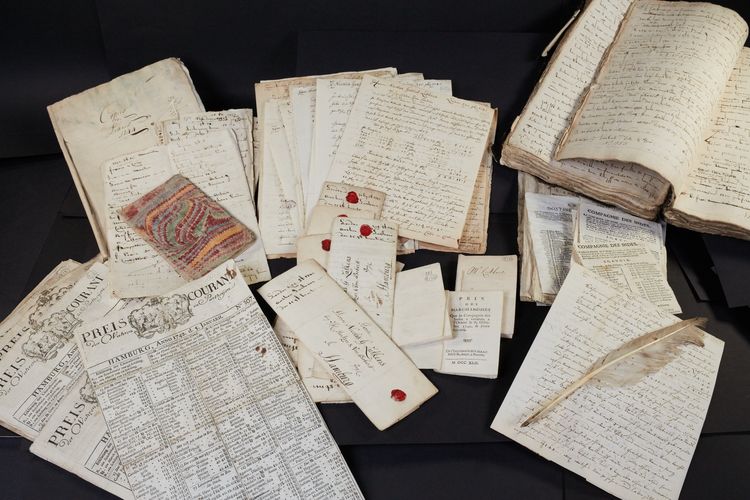

The records of the ships Hoffnung, Franciscus, Juffrouw Elizabeth Galley, De Eendraght, Juffrouw Anna Elizabeth and Jeune Cornelis are particularly rich, appearing as varied and multi-faceted as their authors.

Among the preserved records are more than eighty document types searchable in the data portal, including letters, logbooks, sheet music, bills of exchange, calligraphic exercises, or passports kept on board, as well as letters in Dutch, German, French, or even English. These ships are real treasure troves for researchers and the public.

The case studies presented tell the stories of people living in a world shaped by motion, distress, conflict and colonialism.

We read about the story of a Hamburg merchant, who had travelled and traded for two years in French ‘enemy land’ and whose hidden merchant archive was found by British officers in the bow of a ship. The letters seized aboard the ship Franciscus offer us unique insights into the lives of a wide range of early modern people, from musicians and poets to a young woman living in an English nunnery or an Irish Catholic merchant whose trade linked the Spanish Empire with northern Europe. There is also a story of a ship with an incredible voyage, an escape from alleged Muslim pirates and a crate full of letters that provide a glimpse into the everyday lives of the men and women of Tenerife. In another case, captains pretended to be famous counts from their homeland in German Emsland to protect themselves. Did it work? One collection includes letters that went as far as Prussia and show the links between the region, its hinterland and the world, and we learn about loss and fate in the case of a Bavarian diplomat who, on his way to the birthday of the English king, had all of his clothes stolen.

There are many possibilities for research on these ships and their documents.

Read the court records and ship's papers to learn about the war, the theatre of war at sea, maritime neutrality, international law of the sea and its consequences, or about legal practice and diplomacy, ports and the goods traded and shipped around the world. Discover letters written by people from all walks of life, from merchants to ordinary sailors, and relating to topics such as family, business or seafaring.

Be one of the first to take a look at these newly discovered sources that we have just made accessible to researchers.

Our next case study from the War of the Austrian Succession will feature Spanish ships and their rich cargoes, notorious English captains, and the question of why Portuguese ships were captured, despite Portugal being allied with Britain.

Anna Brinkman-Schwartz

King's College London, Co-director Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies

The prize papers are a treasure trove of material for any scholar or student interested in the history of neutrality, prize law, and strategy. The documents - from court material and legal commentary to the letters and documents of merchants - contained within the collection are one of the keys to understanding the vital connections between law, maritime strategy, and neutrality during the long 18th Century. Delving into this collection will enrich any research project that touches upon economic history, the history of warfare, the history of empire, and maritime history.

Leos Müller

Stockholm University, Scandinavian Prize Papers

Author of Neutrality in World History

Neutral states were key agents in implementing the free trade paradigm in international trade. Neutral maritime states fought for their rights to trade and navigate freely during wartime, with anyone and anywhere. They also employed legal arguments for ensuring the freedom of the sea, and they took steps to enforce their trade rights. […] Neutrality is a strange thing. It has been dismissed as either unrealistic or immoral—or both. But in spite of its long history of being despised, it still is alive and still considered as a foreign policy option.

Anka Steffen

Europa-University Viadrina, The Globalized Periphery Project

Author of A cloth that binds

The Prize Papers offer unique insights into the role of neutral merchants in international trade. The documented examination procedures on the legality of the transfer of ownership of neutral ships, neutral goods, or goods that belonged to trading persons associated with neutral nations bundle all crucial information on the trade transactions planned between all parties involved, belligerents and neutrals. This provides, for example, a rare insight into the trading activities of merchants from neutral 18th-century Hamburg, Bremen or Prussia and their strategies for making the greatest possible profit from overseas trade without being directly involved in it, even, or especially, in times of war. As a collection of sources, the Prize Papers thus often make up for lost archival material on economic actors whose indirect involvement in the trade of colonial goods and even the slave trade would otherwise remain underestimated.