Hoffnung

Vue de l'intérieur du Port de Brest (1795). Painting by Jean-Francois Hue (1751-1823), Paris, Louvre Museum.

This case study was written by Dr Lucas Haasis, based on his book “The Power of Persuasion”, Bielefeld: transcript publishers | Columbia University Press, 2022.

The introduction of the book can be read open access here.

Hoffnung

The Luetkens Archive

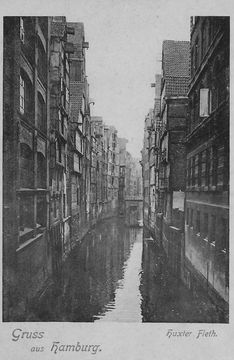

In August 1745 in the French port in Brest the Hamburg merchant Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens loaded his business archive onto one of his ships bound for his hometown Hamburg. Luetkens, who was born in Hamburg Billwerder but apprenticed in the Free and Imperial City of Hamburg, was the son of a priest but his uncles were also successful businessmen. One of those uncles was Joachim Kähler, co-owner of the ship Franciscus.

Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens (1716–1788) had spent the years 1743 to 1745 in France as a travelling merchant, visiting and doing business in the cities connected to the French Atlantic trade, and making a name for himself as a wholesale merchant. France was at war with England in 1745. So when he sent his archive – overflowing with letters from French business partners – through the English Channel to Hamburg, he preferred to play it safe and let the men hide his chest in the ‘afterhold of the ship’. But the hiding place proved inadequate. The ship to which the merchant had entrusted his business archive, the Hoffnung, was captured ‘five Leagues to the Southward of Beachy Head’. British officers found the archive and confiscated it. Luetkens never saw it again.

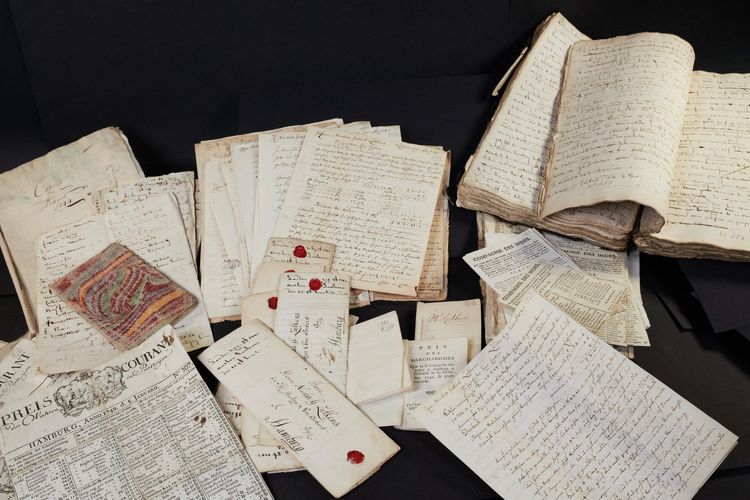

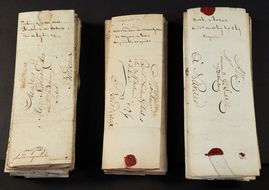

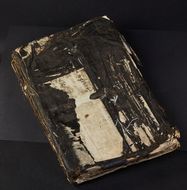

The Luetkens archive is today stored in the Prize Papers collection and offers us unique insights into mercantile life, trade and travel during the eighteenth century. Forgotten for centuries, it has survived in the condition it was in anno 1745. When I found it in 2012, it was still stored in Luetkens’ original ordering system, with dozens of letter bundles stuffed into the boxes, as if he had only just sent it on its way home. This archive is a real time capsule.

Due to the particular moment that it was taken from its owner – only shortly before Luetkens’ return to Hamburg and his impending marriage following two years of travel – this archive takes us right back to one of the most formative and decisive phases in the life of a merchant. It covers the stage between apprenticeship and the opening of one’s own merchant house, a period of mobility and a stage in a merchant’s career in which everything hung in the balance: the mercantile establishment phase. This case study sheds light on some of the fascinating finds from the Luetkens archive and what it can tell us about merchants, France, letters and the eighteenth century.

Discover HCA 30/232: Die Hoffnung in TNA Discovery

continued in HCA 30/233, HCA 30/234, HCA 30/235, HCA 30/236

Browse the documents in the Prize Papers Portal

The Establishment Phase of a Merchant

When the Hoffnung left Brest for Hamburg, Luetkens was already on the finishing straight of establishing himself and settling down as a merchant. As he later wrote in a letter, the aim of his business travel to France had been to ‘to provehimself in trade’ and ‘to make friends and settle some correspondence in foreign lands.’ In other words, the business trip was intended to complete his transformation into a well-established, settled merchant in the Atlantic trade. In 1745 he had already succeeded in this undertaking with an address book full of contacts and his bags ‘full of speciethaler’ (coins). In Hamburg his future wife, Ilsabe Engelhardt, daughter of a respectable Hamburg merchant family, awaited him, together with his future business partner, Ehrenfried Engelhardt. Engelhardt was the brother of his future bride and Luetkens would later open the merchant house Luetkens & Engelhardt with his brother-in-law in the city on the Elbe. Luetkens & Engelhardt would go on to be one of the major sugar importers in Hamburg during the second half of the eighteenth century. The records in Luetkens’ travel archive from 1743 to 1745 document the path that brought him to that point in his career.

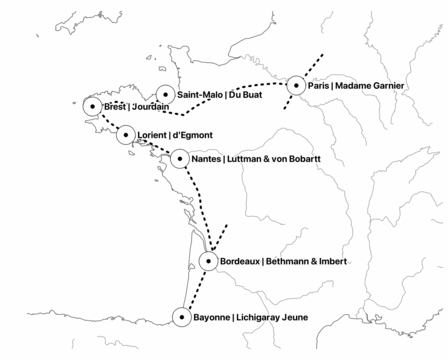

Studying this archive allows for a deeper understanding of crucial career steps taken by wholesale merchants in the establishment phase during the eighteenth century: shipping business, commission trade and high-risk trade as well as founding a merchant house and marriage. It also shows the goals and benefits of merchant travel. Luetkens’ business trip to France led him all the way along the French Atlantic coastline, and he visited all the major ports of French Atlantic trade – Bordeaux, Bayonne, Nantes, Lorient, Brest, St. Malo, Paris – before finally returning to Hamburg by land. In each of the cities, he visited a renowned merchant house, where he found a place to stay and to work for several weeks or even months. This enabled him to gain a sturdy foundation in and experience of the French Atlantic trade, to enter into lucrative enterprises with French merchants and to amass a not insignificant fortune.

A Merchant’s Letters

The letters surviving in Luetkens archive offer a vivid insight into his trading activities and negotiations with his business partners. The Luetkens archive still contains all the letters that Luetkens kept in his chest in 1745. In total it consists of 2,286 letters – both business and personal letters – Luetkens’ large letter book and many other business records. The remarkable thing about the archive is that both incoming and outgoing letters in three languages – German, French and Dutch – have survived. These letters allow the reconstruction of two-sided letter exchanges between correspondents, including over sixty correspondents from whom letters have also survived. As a result, it is possible to not only look at Luetkens as an isolated example of a mercantile career, but to present the Hamburg merchant as a part of a large community and network of European – mostly Protestant – merchants active in the Atlantic trade. A great variety of different letter types and styles are represented in the archive, from personal and love letters, to business letters or letters between brothers. The archive offers us the full range of correspondence practices in the life of a merchant and communication practices amongst the middle class in the eighteenth century.

A Bourgeois Lifestyle

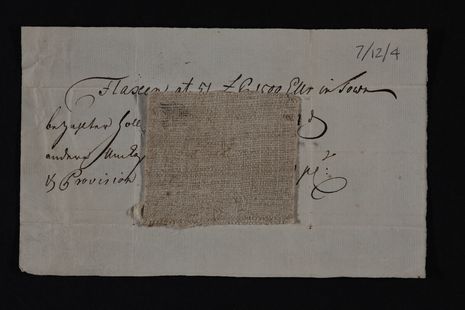

In addition to the letters, various other records have survived, from typical mercantile records such as bills of exchange, bills of lading, accounts or price currents to personal records, such as a small notebook with personal expenses which Luetkens kept during his travels. Based on the items listed in his pocketbook of expenses, it is even possible to reconstruct Luetkens’ outward appearance in the form of a mannequin – similar to the drawing of the Bavarian diplomat presented by Justin Schröder in his case studies. Also preserved are lists of furniture for the future trading house, including a mahogany card playing table, a large, gilded mirror, valuable kitchenware, a chest of drawers and several other items which Luetkens ordered and bought with the help of his brother and shipped to Hamburg. In sum the Hamburg merchant in France ordered a ‘stately interior for a house’. He also sent jewellery to his future wife by letter –unfortunately no longer preserved. All these finds testify not only to Luetkens’ wealth, but also to an upper middle-class lifestyle, which he continued even after his return. In the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, the Bel Etage of Luetkens’ merchant house in Katharinenstraße 17 in Hamburg is still on display today. The furnishings and orders for this house began as early as 1745. Luetkens had the capital necessary to purchase and install into his new house this magnificent golden panelling in the Louis Seize style in France, thanks to his good connections in France. It was these connections that helped his trading house to become a major sugar importer in Hamburg shortly after his return France. The Bel Etage is thus ultimately a contemporary testimony of how a Hanseatic merchant profited from the French plantation economy and the French colonial system. Luetkens actively supported both with his trading activities throughout his life.

A Hamburg Merchant in France

The role that merchants like Luetkens played in the colonial system of the early modern period, in the trade with the colonial superpowers France, Spain, but also England, was that of second-tier colonial merchants. France was an attractive travel destination for many German merchants at the time. Luetkens deliberately chose the French west coast for his establishment phase as a central phase of his career. In France foreign merchants were excluded from direct trade with the French colonies by mercantilist policies – in particular by L'exclusive, which restricted access to direct trade to French merchants – but Hanseatic merchants in French cities nevertheless enjoyed privileges in France and were allowed to participate actively in the French market. They were allowed to settle in France, rent warehouses and establish joint trading houses with French merchants. They were even exempt from customs duties on many goods. The exclusion from direct trade with the French colonies thus did not prevent Hamburg merchants such as Luetkens from travelling to France and trading there. In metropolitan France they engaged in re-export and onward transport of colonial goods to Hamburg and Central Europe instead of direct trade. Almost all onward transport of French sugar, Luetkens specialty, to central Europe went via neutral channels and neutral merchants. Hamburg merchants were allowed in particular to trade in surplus goods that found no buyers on the French market. For the purpose of redistributing French goods during his voyage, Luetkens built up a dense logistical supply and support network as well as a regular shipping connection between Hamburg and the most important transshipping ports in the Atlantic trade.

Merchants like Luetkens were commission agents, logistical middlemen, shipowners and middlemen. Thus their business success was built upon the French plantation system as well as the colonial economy and administration just like the success of the French merchants. These merchants supported and profited from the colonial economies of the time. Several German merchants also participated in the Atlantic slave trade. Luetkens was not involved in the trafficking of enslaved persons, but he still did his part to ensure that the plantation economy prospered. It is significant in this respect that the only artefacts apart from the many written sources preserved in the Luetkens archive today are linen samples and a cotton sample. Linen, especially from Silesia in Germany, was an important good in the triangular trade. Luetkens’ role in it was to distribute and supply these locally produced goods to France.

Read the article “Buying Patience: Ordering and Purchasing Wedding Jewellery and Furniture through Intimate Networks during Eighteenth-Century Mercantile Marriage Initiation and Preparation”, Itinerario, 1-15.

To this day a portrait of Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens hangs on one of the grey walls of the Kleines Zimmer in Hamburg’s city hall, a large three-quarter portrait of a man wearing a robe, a wig and a white ruff, gallantly dangling one of his hands over a chair. The portrait depicts the merchant Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens in his official attire as a senator and as a member of the Commerz-Deputation of the free imperial city of Hamburg in 1776. I own another copy of this portrait.

I hope that one day, through the publication of his letters, through the publication of my book, we will be able to add a plaque to the portraits and thus add an important piece of the puzzle of Hamburg’s history: about Hamburg, one of its merchants and its role in Germany’s colonial past.

Portrait of Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens (1716-1788), engraved by Charles Townley, painted after a model by Rudolf Christian Schade, 1790. Source: privately owned.

by Dr Lucas Haasis

Research Cooperations and PR

Contact: lucas.haasis@uni-oldenburg.de

Follow me on: Orcid, Twitter, Mastodon

I would like to thank my wonderful student research assistants Rieke Marie Kaiser, Luan Cakolli and Gordon Harker for helping me enter the metadata of the hundreds of documents in the Luetkens archive and for sharing my vision. I thank Annika Eileen de Freitas for her continuous support and for creating this homepage. All student assistants are now also working on their own collections in the Prize Papers collection.

Credit: Die Hoffnung, TNA, HCA 30/232, HCA 30/233, HCA 30/234, HCA 30/235 and HCA 30/236, Photo: Maria Cardamone, Mustapha Ousellam, Prize Papers Project. © Images reproduced by permission of The National Archives, London, England.