Case Study: French Prizes

PR Contact: Dr Lucas Haasis

Email: lucas.haasis@uni-oldenburg.de

Prof. Dr Dagmar Freist

Project Director

With the publication of these exemplary ships, we provide an insight into the research potential of the manifold documents surviving as prize papers in The National Archives, UK. More so, we demonstrate the incredible benefit of sorting, cataloguing, digitizing and presenting this vast collection open access for academic research and the interested public which is being made possible by the funding of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities: For the first time, researchers can search the prize papers on document level, on a large scale, and they can establish various relations between documents, captures, court processes, actors, time and place in this beta version of the Portal.

Dr Amanda Bevan

Head of Legal Records and Head of the National Archives' Prize Papers Team

We have uncovered the stories of ships captured by the Royal Navy and privateers in the wars of the 1740s. Any letters on board, for delivery across the seas, were confiscated: the Prize Papers Project is virtually delivering them to and across the world, nearly 300 years later.

Case Study: French Prizes

Over the course of 2022 and 2023, the Prize Papers Project will publish representative case studies of documents that were found aboard captured ships seized by the British during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). We will present our first selection of exemplary records along with the corresponding court records. The purpose of these case studies is to introduce our visitors to the richness, character and diversity of the Prize Papers collection. All these papers are held in the series HCA 30 and HCA 32 at The National Archives, UK. The documents will be made available online for the first time as digital images with metadata on our open access data portal. The first case study is related to French prizes, ships captured by the English from their French opponents during the War of the Austrian Succession. The background to these fascinating time capsules is presented on this homepage.The next case studies look at neutral ships captured during the war and why this was possible in the first place.

Between 1740 and 1748, many parts of the world were shaken by the War of the Austrian Succession.

This war began with the invasion of the Austrian province of Silesia by King Frederick II of Prussia after the death of Emperor Charles VI, which raised the open and controversial question of the legitimacy of his daughter Maria Theresa's succession to the Habsburg Austrian crown. The conflict soon led to a series of events that resulted in a war in Europe, America, Russia, India and the Caribbean. The war was fought fiercely both on land and at sea. While the war on land was primarily characterised by Franco-Austrian rivalry and fought over territorial and political claims to power, the war at sea raged as a colonial conflict over naval supremacy at home and in the colonies. On land, the Habsburg Monarchy, Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, Hanover and their allies were at war with France, Prussia, Spain, Bavaria and their allies. The war at sea mainly involved two colonial powers: Britain and France, which fought each other between 1744-48. The War of the Austrian Succession ended in 1748 with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, confirming Maria Theresia as the Empress and leaving the naval powers Britain and France in a stalemate with a slight advantage for Britain. The Franco-British rivalry continued during the Seven Years' War.

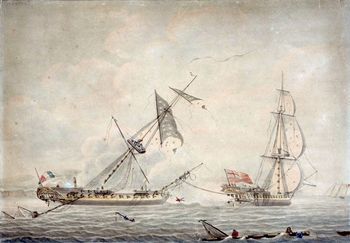

One of the most important war tactics during the War of the Austrian Succession at sea was ship capture.

The captures were carried out by both French and British ships. Legitimised by naval warfare and the law of war, capture, i.e. the seizure of enemy ships, was a common tactical warfare throughout the early modern period. The navies as well as the privateers were both involved in this practice. Privateers were captors from the private sector who were legitimised by the crowns through letters of marque to capture enemy ships. These ships served as auxiliaries to the royal naval forces. During the 18th century, the defence of one’s own maritime trade as well as the weakening of the enemy’s economy by disrupting his supply lines were still common objectives of tactical naval warfare. Privateers were used for the latter purpose. In addition to naval battles, such as the battles of Cape Finisterre, Havana or Toulon, and sieges, as, for example, the sieges of Madras or Pondicherry, raids and captures played a decisive role during the War of the Austrian Succession, both in domestic waters and in the colonial territories at the time. The sheer number of captured ships reflects the importance of the raids during the war: 3238 on the French, 3434 on the British side.

In the portal, we are now publishing the records of ten of the ships captured by the British.

The ship routes reflect the global nature of the Prize Papers collection and the wide range of prize-taking activities. The ships sailed from Bayonne to Havana and Martinique, from Martinique to Bordeaux, from Leghorn (Livorno) to London, from Cap Francois, Saint Domingue to Bordeaux, from Guinea via Leogane, Saint Domingue, to Nantes, from Caracas to Cadiz and then to Bayonne. All ships were captured in the Atlantic or the English Channel.

According to the provisions of maritime law and the law of war, the legality of a ship capture was established in court by proving that the ship or its cargo belonged to a declared enemy. In the case of French-flagged ships captured during the War of the Austrian Succession, many cases were resolved relatively quickly. As enemy ships, they were “condemned as prize” by the British High Court of Admiralty. The goods and the ships were put to auction. The surviving documents of these court cases are therefore mostly limited to the court records (CP) and the original ship's papers (SP) or abstracts and translations of the ship’s papers that were used as evidence in court. In addition to these more routinised cases, the Prize Papers collection also includes many more complex cases from which more diverse documents have survived.

Three of these ships are presented in detail on this page.

These ships represent special cases proving that not all French prizes were sure-fire-successes. In some instances, more evidence had to be collected from aboard the ship by offloading its cargo and papers in order to receive further investigation. This was done if a case was disputed, the ship contained goods that could be claimed by non-belligerent neutral parties due to the ownership being unclear, or the case involved a recapture. Among the ships presented in the portal, there is an English ship that had been captured by the French and recaptured by the British, a typical example of the turmoil of war. This ship was not condemned as prize, but instead was restored upon payment of 1/3 salvage money.

The records of L’Amphitrion, La Diligente and The John and Constant are more extensive and feature a wide variety of documents.

The surviving records include several of the 82 document types searchable in the data portal, including logbooks, manuscript books, arithmetic instruction book, bills of health relating to quarantines, and mail-in-transit stored on board with letters in French and Spanish and further records in English or Italian. These ships are true treasure troves for research and the public.

There are many possibilities to do research on these ships.

Read the court records and ship's papers to learn about the war, the theatre of war at sea and its consequences, about legal practice or diplomacy, or about French ports and the goods traded and shipped around the world, including objects, such as elephant teeth or coins. Discover letters written by people from all walks of life, from merchants to ordinary sailors, from husbands to wives, between business partners or friends, relating to topics such as family, business, seafaring or slavery. You can even discover letters dictated by illiterate sailors. Be one of the first to take a look at letter packets that are now being made accessible for research and cataloguing purposes for the first time and still show original letterfolding techniques.

Prof. Dr Pierrick Pourchasse

Université de Bretagne Occidentale (UBO) Brest

Some historians refer to all of the military conflicts between France and England from 1689 to 1815 as the Second Hundred Years War. The Prize Papers portal provides access to the documents seized from the thousands of French ships captured by the British during these conflicts. This exceptional source can be used for research in many fields, whether economic, political, social or cultural.

Dr Myriam Bergeron-Maguire

Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris

Private letters are known to be a source which is as close as we can get to informal registers in the histories of our languages and therefore, to be exceptionally beneficial for the study of historical variation and linguistic change. Including thousands of letters written in many languages, the Prize Papers portal will make unprecedented data available for Historical Sociolinguistics and Historical Linguistics altogether.

Dr Éva Guillorel

Université Rennes 2

Documents seized from French ships by British privateers in the seventeenth and eighteenth century are incredibly rich and diverse. Online collections from HCA 32 provided on the Prize Papers Portal offer splendid opportunities to develop new research in many disciplines. They are also a precious resource when it comes to complementing previous studies since they greatly facilitate comparison with sources related to the same ships which are being held in French archive centers.

Siem van Eeten

Independent researcher and author | Global Privateering Project

The Prize Papers are one of the most precious time capsules discovered in the last decades. Relating to the British Empire they reveal an incredible quantity of aspects from the 17th, 18th and parts of the 19th century. They are also valuable for understanding the history of France, the Netherlands and many other nations of the early-modern time. And they are an example for the disclosure of prize papers hidden in other archives around the world as, for instance, in the French archives, which will soon be shown as part of the Global Privateering Project.