La Nuestra Señora de Covadonga

PR & Coordination Case Studies:

Dr Lucas Haasis

E-Mail:

Literature recommendations:

Walter, Richard, (1716?-1785), “A voyage round the world, in the years MDCCXL,I,II,III,IV. By George Anson, Esq; commander in chief of a squadron of his majesty's ships, sent upon an expedition to the South-Seas ...”, (London: John and Paul Knapton, 1748).

Vernon, Edward, 1684-1757. “Original papers relating to the expedition to Carthagena.” (London: M. Cooper, 1744),

Eslava, Sebastián de, “Diario de todo lo ocurrido en la expugnación de los fuertes de Bocachica, y sitio de la ciudad de Cartagena de las Indias”, (Instituto Cervantes, Original publication, 1741).

Voltaire, Siècles de Louis XIV: et de Louis XV, Volumes 3-4 By Voltaire, Pierre Didot, et Firmin Didot (1817).

Barrow, John, Sir, “The Life of George, Lord Anson, Admiral of the fleet, Vice-admiral of Great Britain, and First Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty, previous to and during, the Seven Years' War”, (London : J. Murray, 1839).

Rodger, Nicholas Andrew Martin, “Anson, George, Baron Anson," In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (24.05.2008).

Lynch, John, “Bourbon Spain, 1700-1808”, (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: B. Blackwell, 1989).

Lambert, Andrew, “Seapower states – Maritime Culture, Continental Empires and the Conflict that Made the Modern World”, (Ceredigion: Yale University Press, 2018).

Guimerá Agustín, Chaline, Olivier, “La Real Armada : la Marine des Bourbons d'Espagne au XVIIIe Siècle”, (Paris : Sorbonne Université, 2018).

Guadalupe Pinzón Rios, “Defensa del pacífico novohispano ante La presencia de George Anson,” In Ehn 38, (Jan-June 2008), (pp. 63-86).

Katherine Parker, “Charting and Knowledge in Enlightened Empires: The Case of Tierra del Fuego,” In Anson’s Voyage Round the World (1748), The Cartographic Journal, 57:4, 353-365, (2020). DOI: 10.1080/00087041.2020.1884431

Glyn Williams. “George Anson’s Voyage Round the World: The Making of a Best-Seller” In The Princeton University Library Chronicle 64, no. 2 (2003): (pp. 289–312).

Klooster, Wim. "4. Inter-Imperial Smuggling in the Americas, 1600–1800" In Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500-1830 edited by Bernard Bailyn and Patricia L Denault, 141-180. Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2011.

La Nuestra Señora de Covadonga

Nine Spanish ships, captured during Anson’s expedition against the Spanish Armada, including the Nuestra Señora de Covadonga, are now part of the Prize Papers’ digital collection.

Discover HCA 32/135/8: La Nuestra Señora de Cabodonga in TNA Discovery

Browse the documents in the Prize Papers Portal

George Anson’s Archives (I)

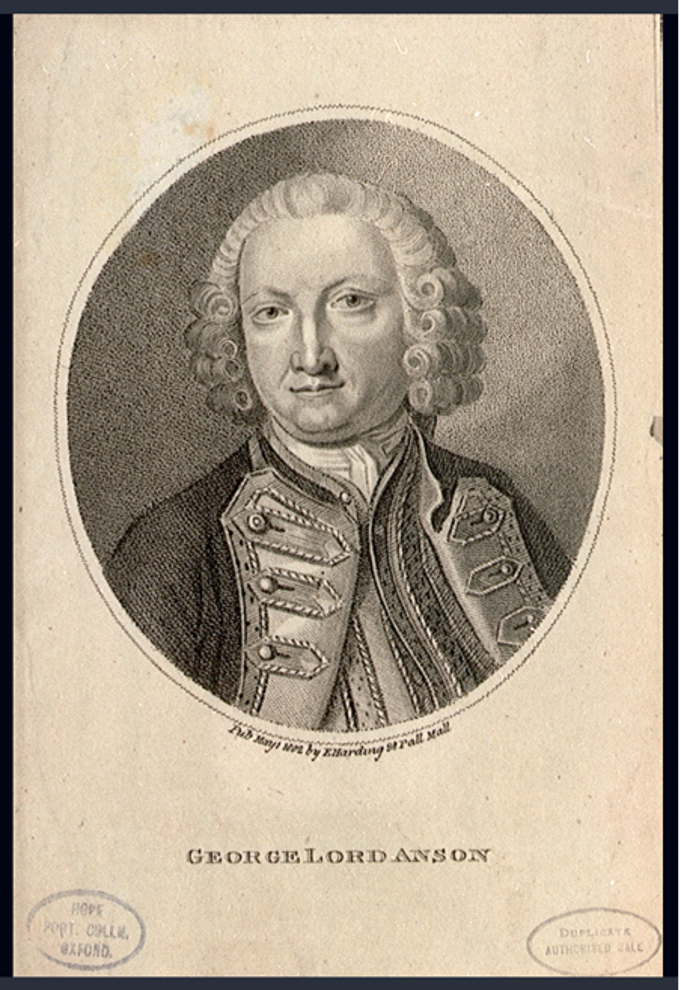

Born into a wealthy family, George Anson (Colwich, 23 April 1697) began his maritime pursuits at an early age. The fortune he earned from the Manila Galleon Nuestra Señora de Covadonga transformed him into a symbol of the burgeoning maritime power state, which counted on the support of the City of London. Anson's career inspired several others to venture eastward in the 18th century.

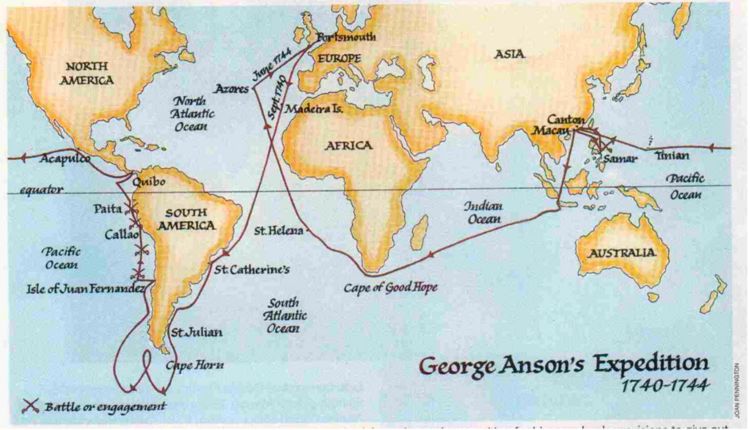

Anson rose to the rank of Commodore after having been an impressive commander in the early stages of the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739-48) in the Caribbean – a conflict that would later merge with the broader War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). Leading a branch of the expedition approved by the Parliament against Bourbonic interests in the South Seas, Anson engaged in privateering and prize-taking as part of the common strategy. While Edward Vernon headed to Portobello to strike against Cartagena, Anson’s journey took him around Cape Horn towards Peru. However, his military ambitions turned this expedition into the twelfth world circumnavigation.

Anson’s squadron was based in Portsmouth and comprised of six warships, two supply ships and 1,900 men upon their departure in September 1740. Nevertheless, they encountered challenging circumstances while navigating the Atlantic.

An outbreak of scurvy forced them to dock in Santa Catharina, Brazil, resulting in the loss of more than half of the crew (1,400 men), including senior officers recruited in Greenwich. Furthermore, this stopover in Brazil exposed Anson’s squadron to the enemy. The local authority, Portuguese José Sylva de Paz, found an opportunity to inform Joseph Pizarro about his fleet, envisioning their shared interests in smuggled bullion. According to Richard Walter, author of Anson’s expedition narratives, he explains the negotiation of Brazilian gold for Peruvian silver, describing an estimated illegal amount involved that indicates the British whole estimate for the circulation of Spanish silver.

Pizzarro's Armada awaited in the River Plate, also grappling with scurvy. Yet, the dispatch influenced their decision to head towards the Pacific. Anson’s archives expose the Spanish supportive network in the Americas.

Both commanders would find difficult to cross the Strait of Magellan, as cartographical references were limited at that time. It is known that due to the tide, Pizarro delegated that stretch of his expedition to another commander, continuing his voyage terrestrially.

Anson arrived in the Pacific after four ships were damaged or destroyed against the rocks. Still, he partook in the political unrest in the surroundings of Nueva Granada with the remaining vessels. Smaller captures, such as the Nuestra Señora de Aranzazu, served as part of his fleet for a while. However, after the Siege of Cartagena in 1741, the British were forced to retreat. This is when Anson decided to capture a Spanish galleon loaded with silver bound for the Philippines and that it would be wiser for him to return via the Pacific.

Knowing that the Nuestra Señora de Covadonga had left Acapulco on 15 April 1743 bound for Cavite, Anson advanced the Centurion to the Marianas. A stopover on the resourceful and deserted Tinian Island permitted further explorations of the Chinese seas. That stretch of his expedition included victualling in Macao and Batavia, where Dutch forces joined his crew.

Hence, Anson returned to the Philippines with the intention of engaging the Covadonga, an encounter that transpired on 20 June 1743. Most Spaniards had assumed that Anson had already returned to England.

The battle lasted for an hour and a half; the Spanish surrendered after experiences approximately 58 casualties (out of 550) and 84 wounded. Despite the precautions taken against potential adversaries – the galleons had been progressively militarised, and that year’s cargo was shared with another vessel - the Covadonga proved to be too heavy. Consequently, Anson’s agility and the advanced British naval technology favoured the Centurion. In the conflict, two sailors (out of 240) perished, and 16 sustained injuries.

Anson brought the Covadonga to Canton, where the interrogations took place, legitimising his ownership of approximately one million pieces of eight – the Spanish dollar. Moreover, he was already well-acquainted with the commerce there, particularly with the Mandarins. A remarkable detail is that Anson managed to avoid paying the mandatory taxes imposed on foreigners after he convinced the emperor that that rule should not apply to war prizes. This was another achievement to conclude his expedition.

While the Covadonga was sold in China, the Centurion was refurbished for a glorious return. Upon returning to Britain, Anson did not share the prize with the King, but distributed it partially among some crew members.

Anson’s papers which once justified his entitlement to the prize’s ownership in court, remained untouched for nearly 300 years. These historical treasures document legal procedures and provide rich details about the Spanish antagonists, allowing for innovative recollections of these disputes.

British narratives on the early 1740s Anglo-Spanish disputes gained popularity through works like Anson’s expedition “A Voyage round the World, in the years MDCCXL, I, Il, Ill, IV (...) by Richard Walter [and Benjamin Robins].” First published in 1748, Walter compiled the episodes of the expedition into an adventurous literary genre that was successfully reproduced and translated.

Moreover, they included 42 charts that contributed to cartographical debates on empire, world-making and accurate representation of remote regions such as Tierra del Fuego during the 18th century.

The Spanish narratives on these events seem less explored, even though Spanish Archives hold fascinating records. Yet, they primarily address the “before and after” of these encounters, principally reporting the Covadonga’s losses.

Therefore, the Prize Papers will supplement the gap in Spanish records, by providing the opportunity to envision their encounters in motion, adding complexity to their narratives.

To highlight two themes found in the sources presented here: Firstly, there are fragments of evidence regarding British procedures concerning “Law and propriety." Secondly, the exploration of “The strategic value of information” aims to unveil the intricacies of Spanish defence.

“Law and propriety in war”

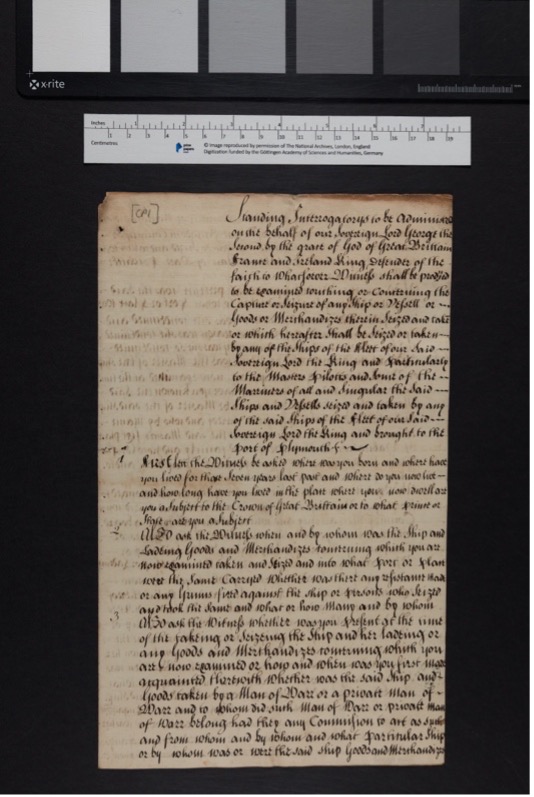

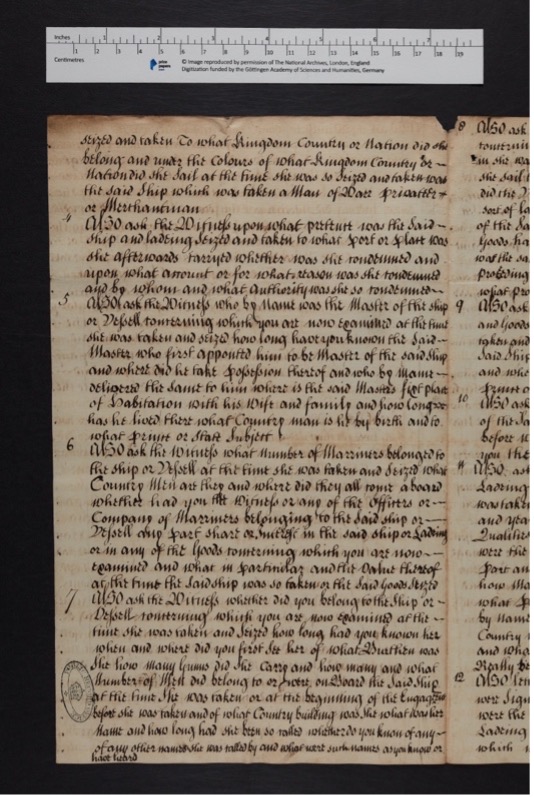

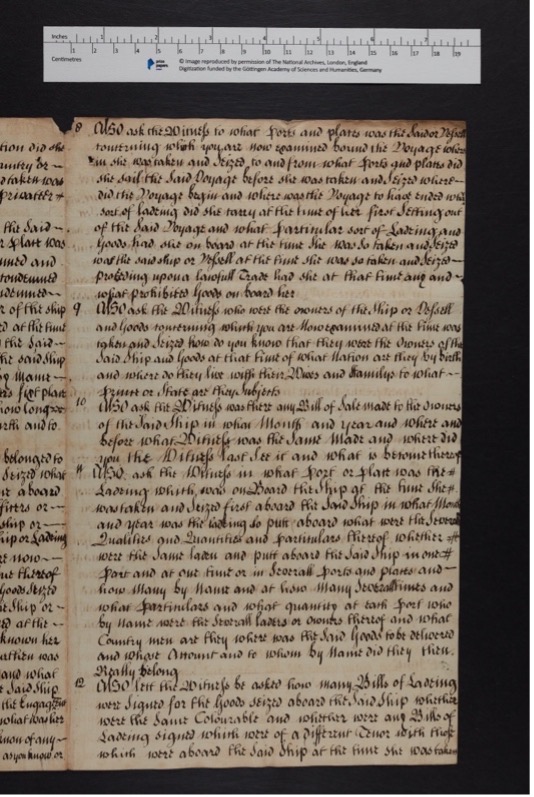

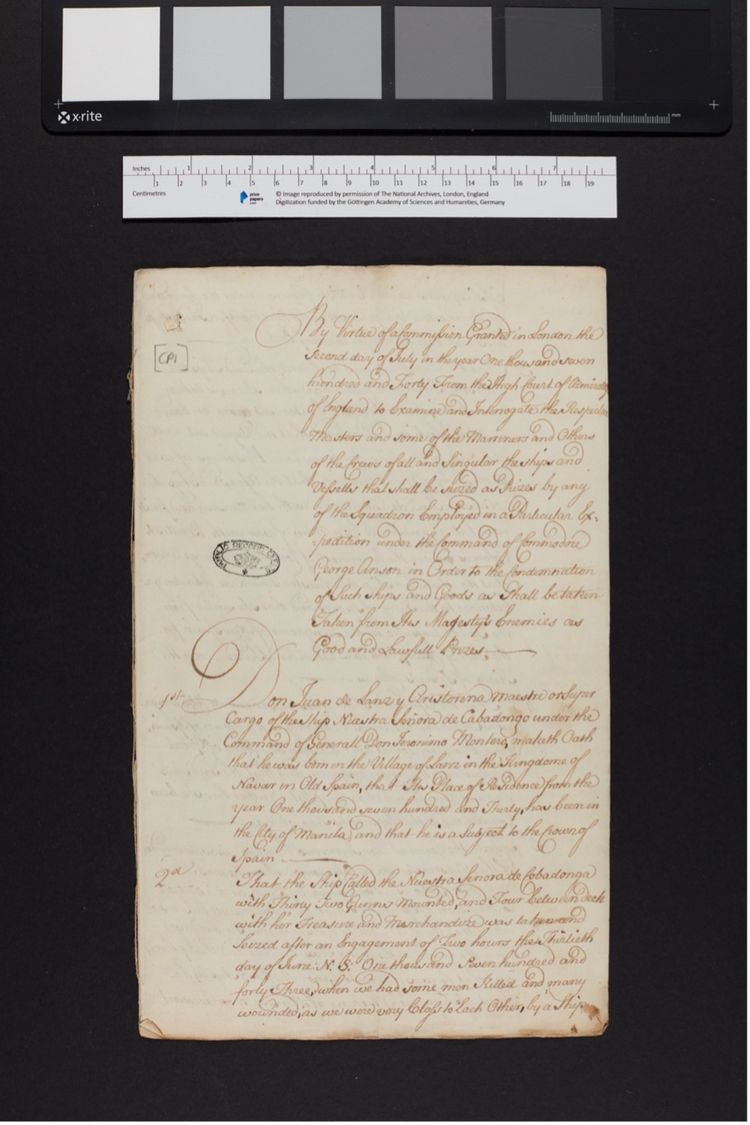

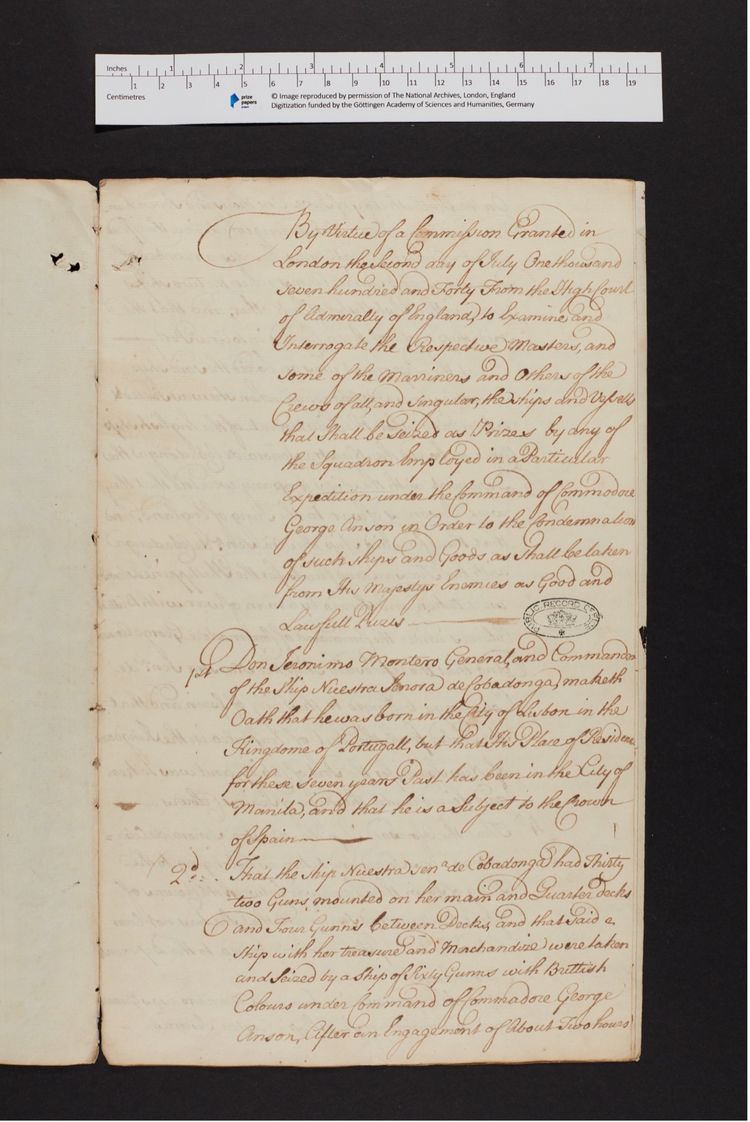

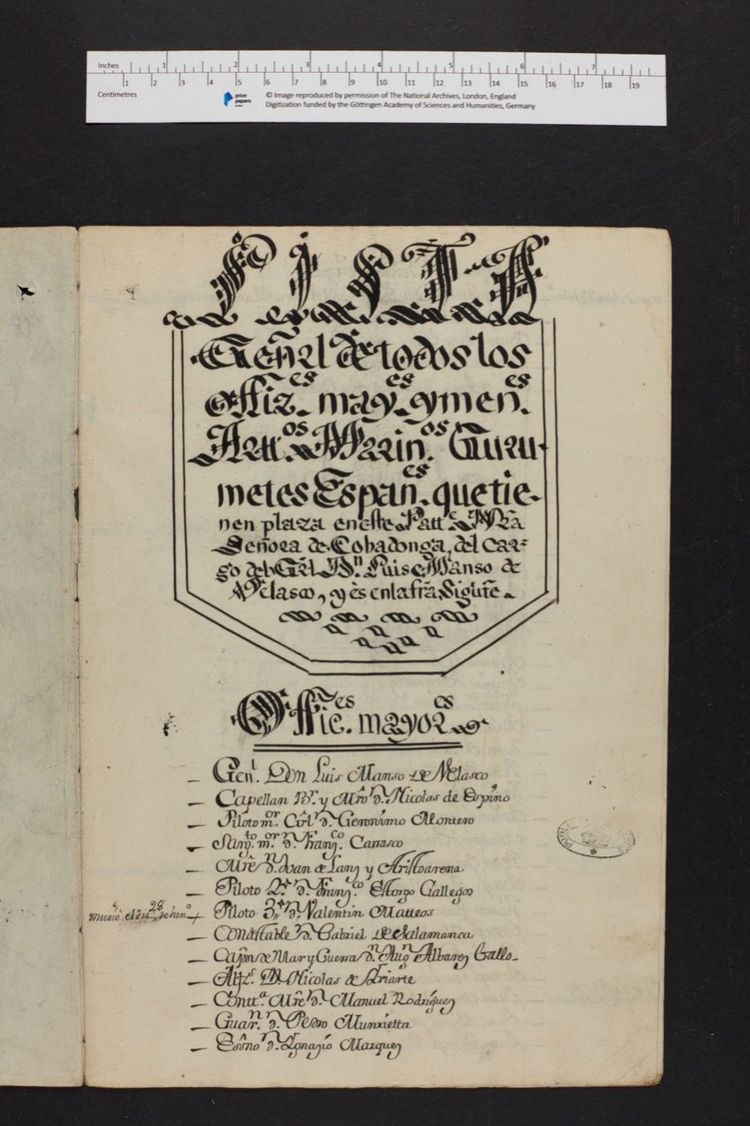

The Nuestra Señora de Covadonga’s “Interrogations and ships papers” depict the British procedures for assessing the goods - primarily based on silver – and provide insights into Spanish logistics. The officials garnering the information sought to confirm the cargo manifest and values described in the Register.

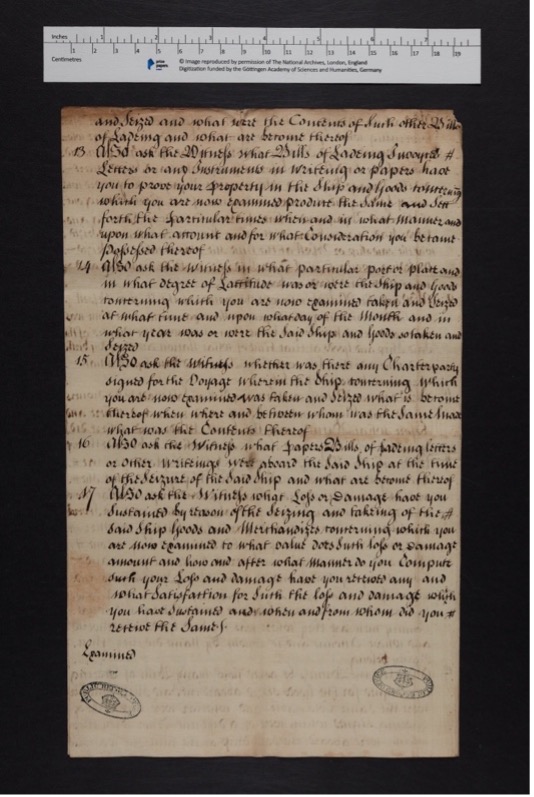

The court papers adhered to a guideline for the interrogations/depositions, similar to the model found amongst those of the ship Prudente Sara de Havana (HCA 32/142/34).

Regarding the Covadonga’s papers:

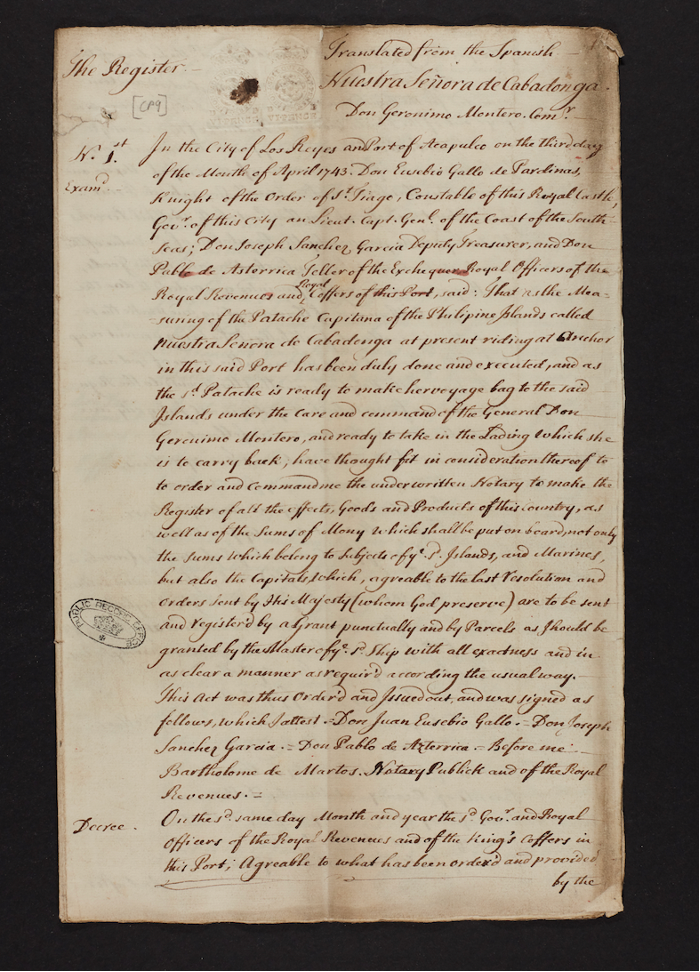

Translation (Register), HCA 32/135/8, CP9

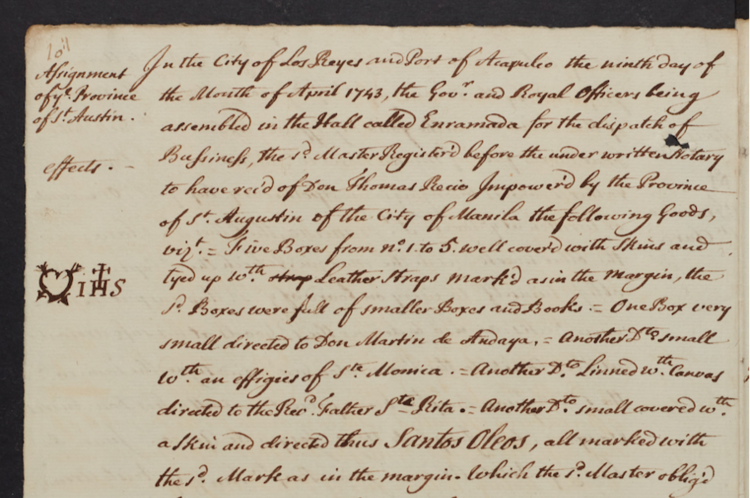

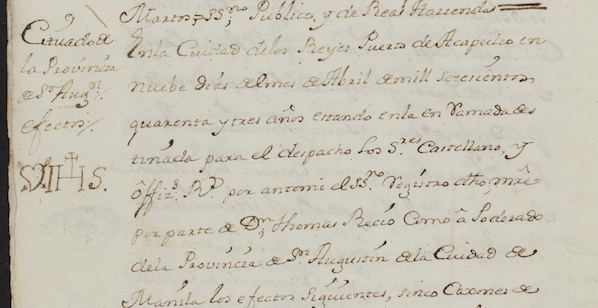

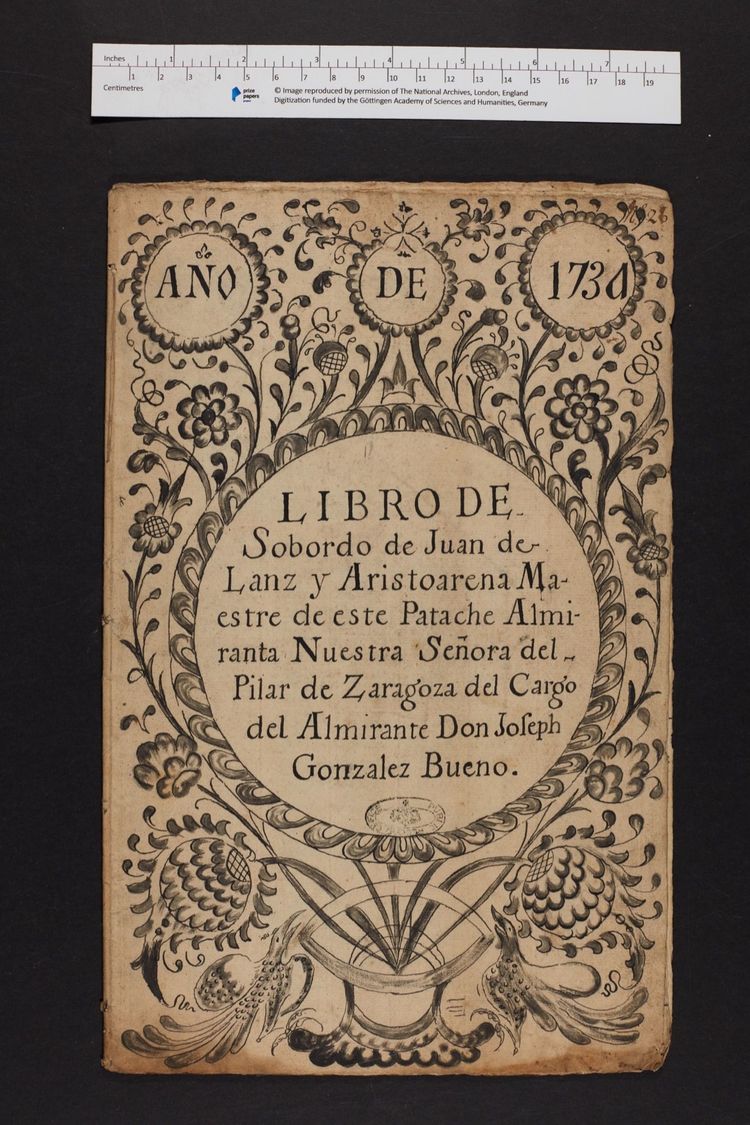

The first translated document, “The Register,” carefully replicates the symbols for identifying the propriety ownership and goods loaded in containers and boxes. See, for example, symbols of the Church belongings entrusted to Lanz y Aristoarena (page 10).

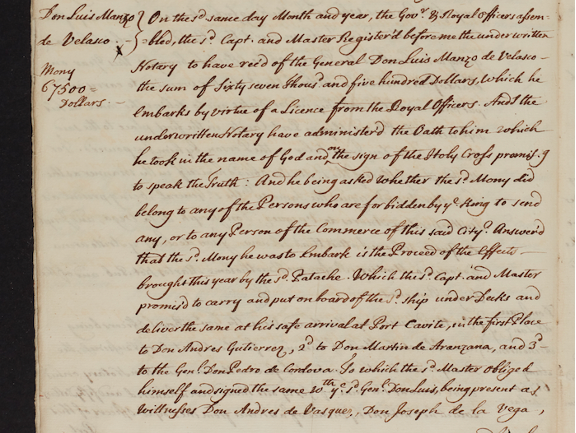

On page 15, the “Assignment of the Government of Mariannas & the Rest of the King’s officers… paid at the Presidium of the Mariannas" ("Mony. 17878 Dolls 4 Reals.”).

This excerpt (from the Register) indicates the British focus on confirming the amount left in The Marianas before the Covadonga’s capture.

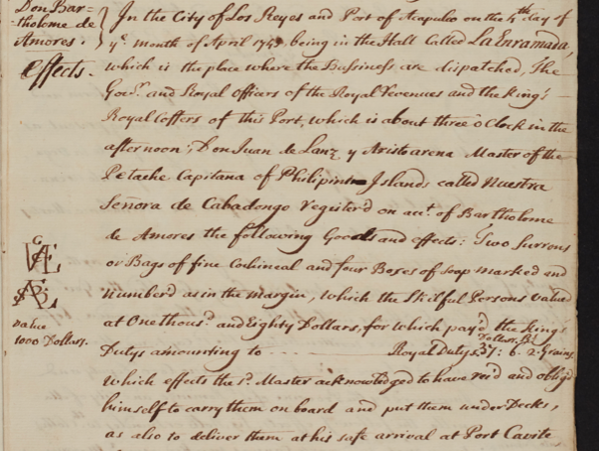

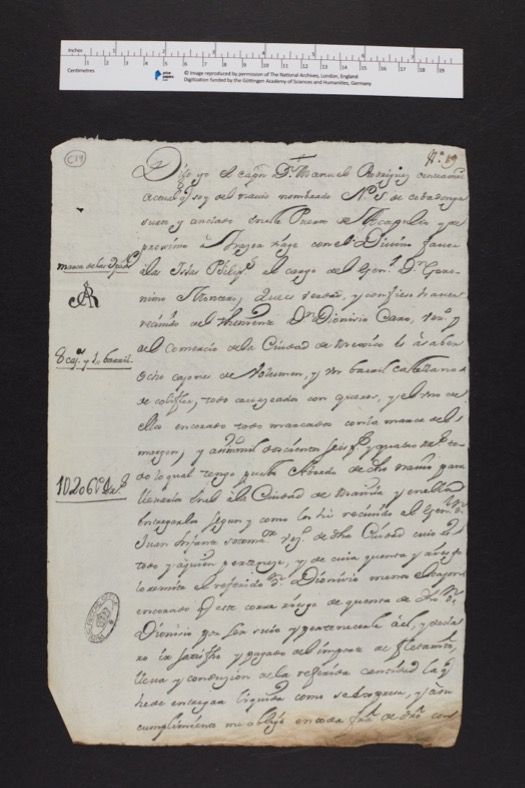

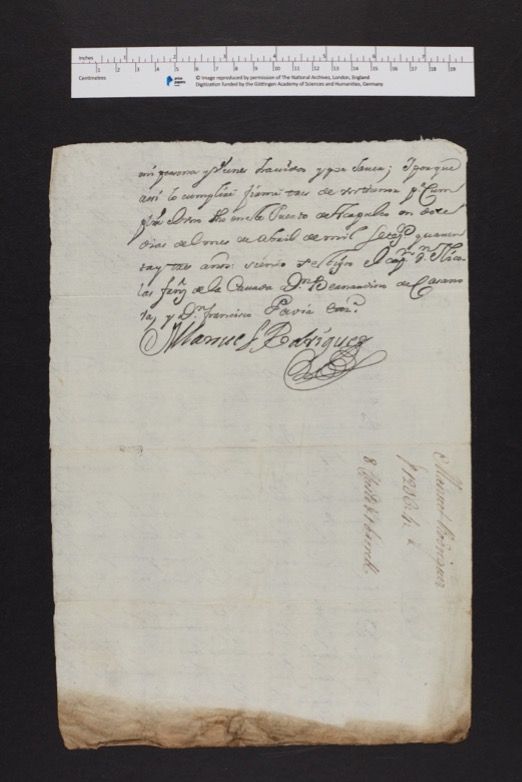

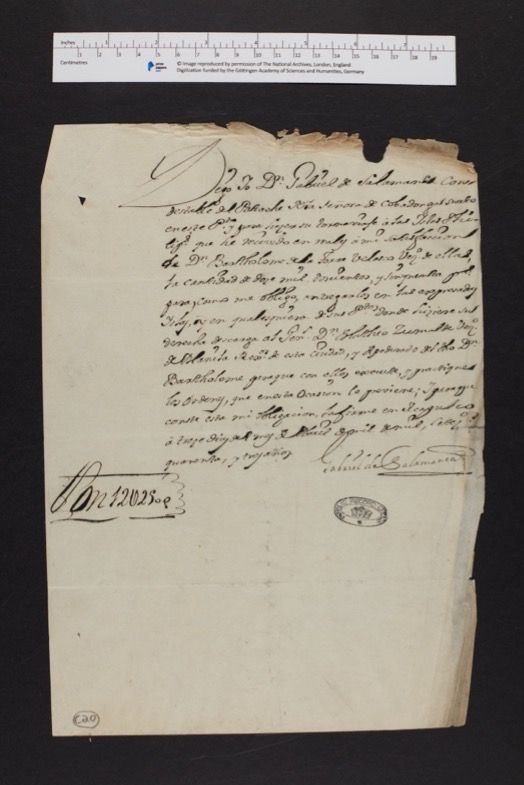

Bills of lading, HCA 32/135/8, CP19, CP20

Receipts and bills of lading also mattered; they should match the Cargo Manifest and Registry to avoid undeclared items.

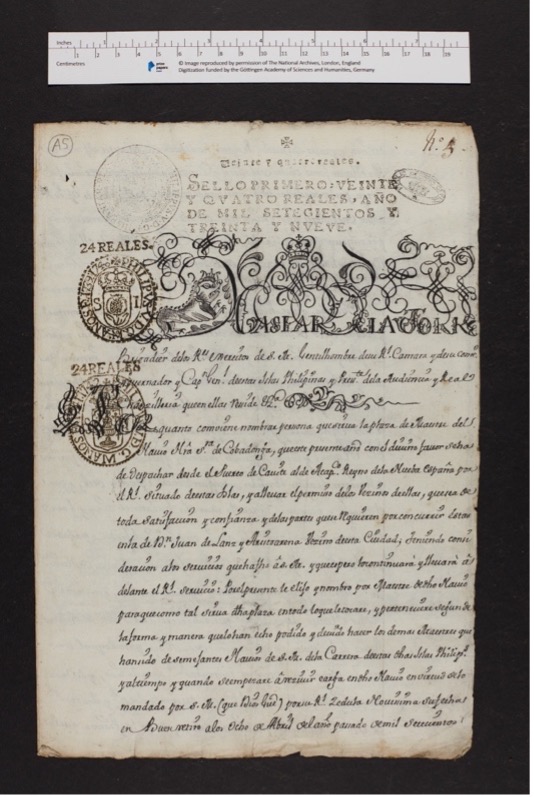

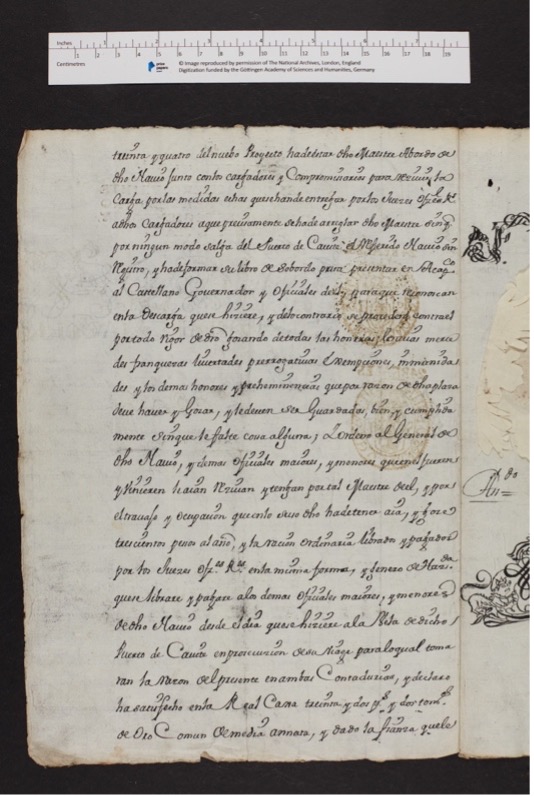

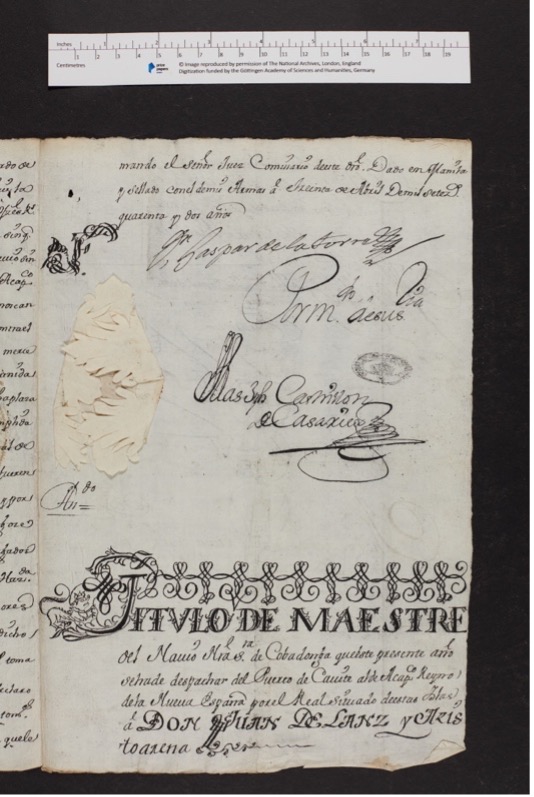

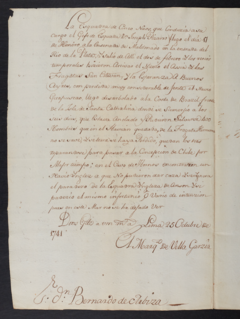

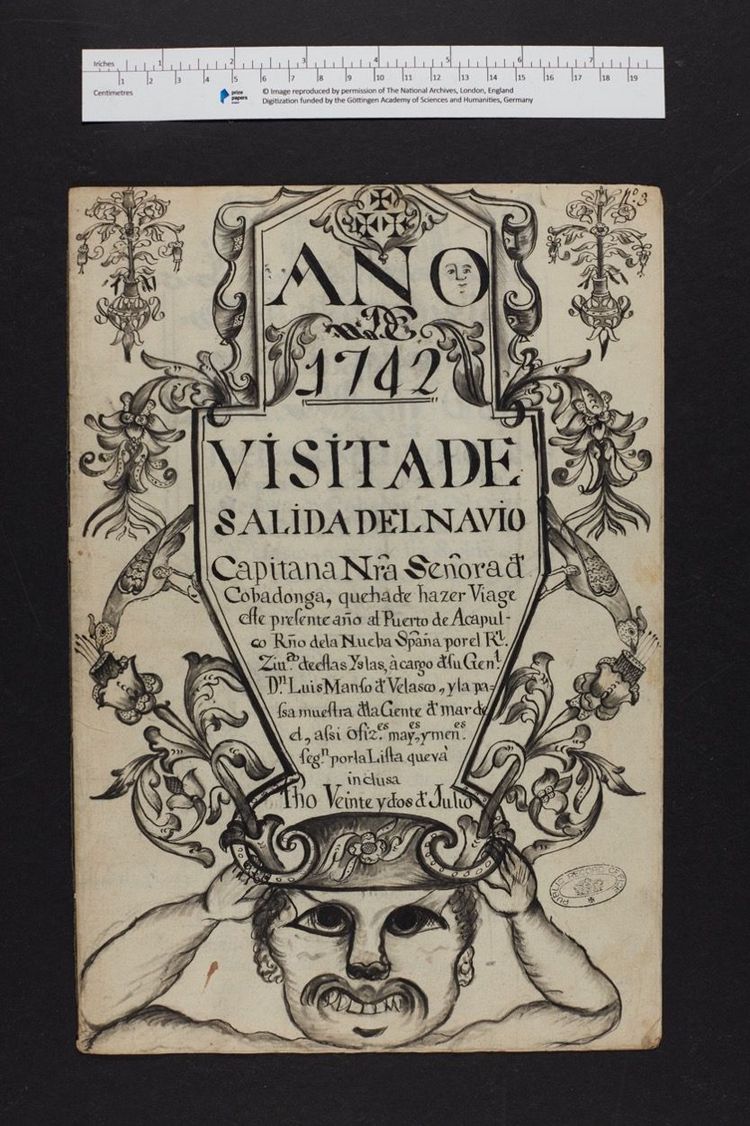

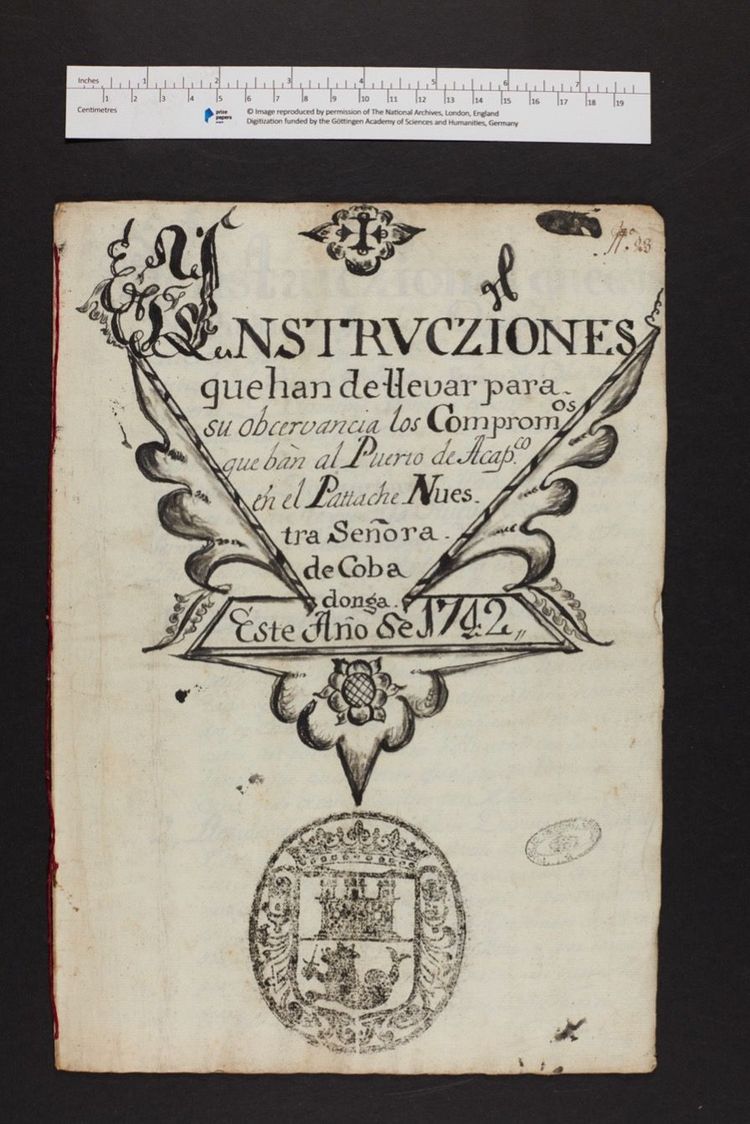

Commission, HCA 32/135/8, A5

Official Spanish documents such as this “Commission”, issued to Juan de Lanz y Aristoarena in 1742, visually display their administrative importance.

Commission issued to Juan de Lanz y Aristoarena in 1742 for “Master of the Nuestra Señora de Covadonga” (“Titulo de Maestre”) by Gaspar de la Torre, signed in Manila, 30 April 1742.

“The value of strategic information”

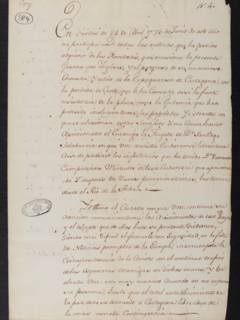

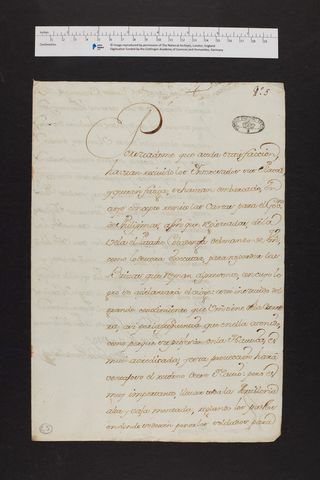

Letters seized in smaller ships captured by Anson reveal the participation of multiple actors in providing information about the British and the ongoing war. The Spanish authorities used commercial ships to extend their communications in Nueva España. Now the Prize Papers unveil how they managed and disseminated information. Shreds of evidence about Anson’s fleet reverberated in the correspondence.

As shown in this letter from Marquez de Villa Garzía, sent from Lima to Bernardo de Arbiza in Valparaiso, Chile, on 25 October 1741:

Letter, HCA 32/134/8, SP4

“La esquadra de cinco nãos que conduzia a su Cargo el Jefe de Esquadra Dn Joseph Pizarro llego el dia 17 De henero a la ensenada de Maldonado em la entrrada del rio de la Plata y Salio de alli el dos de febrero y los recios temporales hizieron arrivar el navio el Assia y las fragatas San Estevan, y la Esperanza a Buenos Ayres, com perdida muy considerable delante el navio Guapuscao,llegó desarbolado a la costa de Brazil frente de la Isla de Santa Catalina donde se sumerjio a los seis dias que estava andado y pudieros salvarse 400 hombres que em el habían quedado de la fragata Hermiona no se save, y se teme se haya perdido, que son los tres reparando-se para passar a la Concepción de Chile por mejor tempo, en el Cabo de Hornos encontraron un navío inglés a que no pudieron dar caza y se ignora el paradero de la escuadra Inglesa de Anson y si padeció el mismo infortunio o vario de intensión pues en este Mar no se ha dejado ver.“

Translation into English:

“The squadron of five ships led by the Commander Joseph Pizarro, arrived on 17 January at the Maldonado bay at the entrance to the River Plate and left there on February 2nd and the strong storms made necessary to the ship Assia and the frigates San Estevan, and the Esperanza to Buenos Ayres, with a very considerable loss of the ship Guapuscao, arrived dismasted on the coast of Brazil in front of the Island of Saint Catherine where it submerged six days after it had been sailing. Hence, 400 men who remained from the frigate Hermiona, which is still unknown, and it was considered that they had been lost, as the three were repairing to travel to Concepción de Chile in a better weather, in the Cape Horn they found a English ship that they could not shelter and the whereabouts of Anson's English squadron are unknown and whether it suffered the same misfortune or a different one because in this Sea they have not been seen.“

As previously noted, Anson’s required stopover in Santa Catharina was subsequently reported to the Spanish. In this account, sent almost one year after Anson departed from England, Villa Garzía commented that part of Pizarro’s fleet had been in Santa Catharina and encountered approximately 400 men who were part of Hermione’s crew. Furthermore, the author commented that in the crossing of the Horn, they came across the remaining English ship but could not determine the direction Anson had taken.

The following letters also demonstrate the Spanish collective concern for the British threat.

Letter, HCA 32/134/5, C5

Letter, HCA 32/134/5, D9

Letter from Miguel de Bustamante, Oaxaca, 1 March 1743, to D. P. Juan de Bustamante Velarde - Manila:

This personal letter sent from Miguel de Bustamante, an uncle based in Oaxaca, to his nephew Juan in the Philippines, displays the circulation of spontaneous communications during times of war. Alongside his commentaries on tokens of affection, such as the chocolate sent to his family, Bustamante describes the local impacts of war such as disrupted commerce and the absence of incoming goods and ships.

To conclude, it can be observed that the smaller ships carrying strategic correspondence ended up being strategic for the British. When read chronologically, letters intercepted in the eight smaller prizes can shed light on the events leading to the Covadonga’s capture. They offer insights into the circumstances within the American context that facilitated Anson's planned attack on the Manila Galleon in the Philippines in 1743.

by Marilia Moreira

School of Advanced Studies (SAS), University of London

Contact:

with the help of Rieke Marie Kaiser

The author of the case studies is responsible for the content and for image licencing. The Prize Papers Project assumes no liability.